In the Month of the Midnight Sun

Stockholm 1856. An orphaned boy brought up to serve the state as a man. A rich young woman incapable of living by the conventions of society. Neither is prepared for the journey into the heat, mystery, violence and disorienting perpetual daylight of the far North.

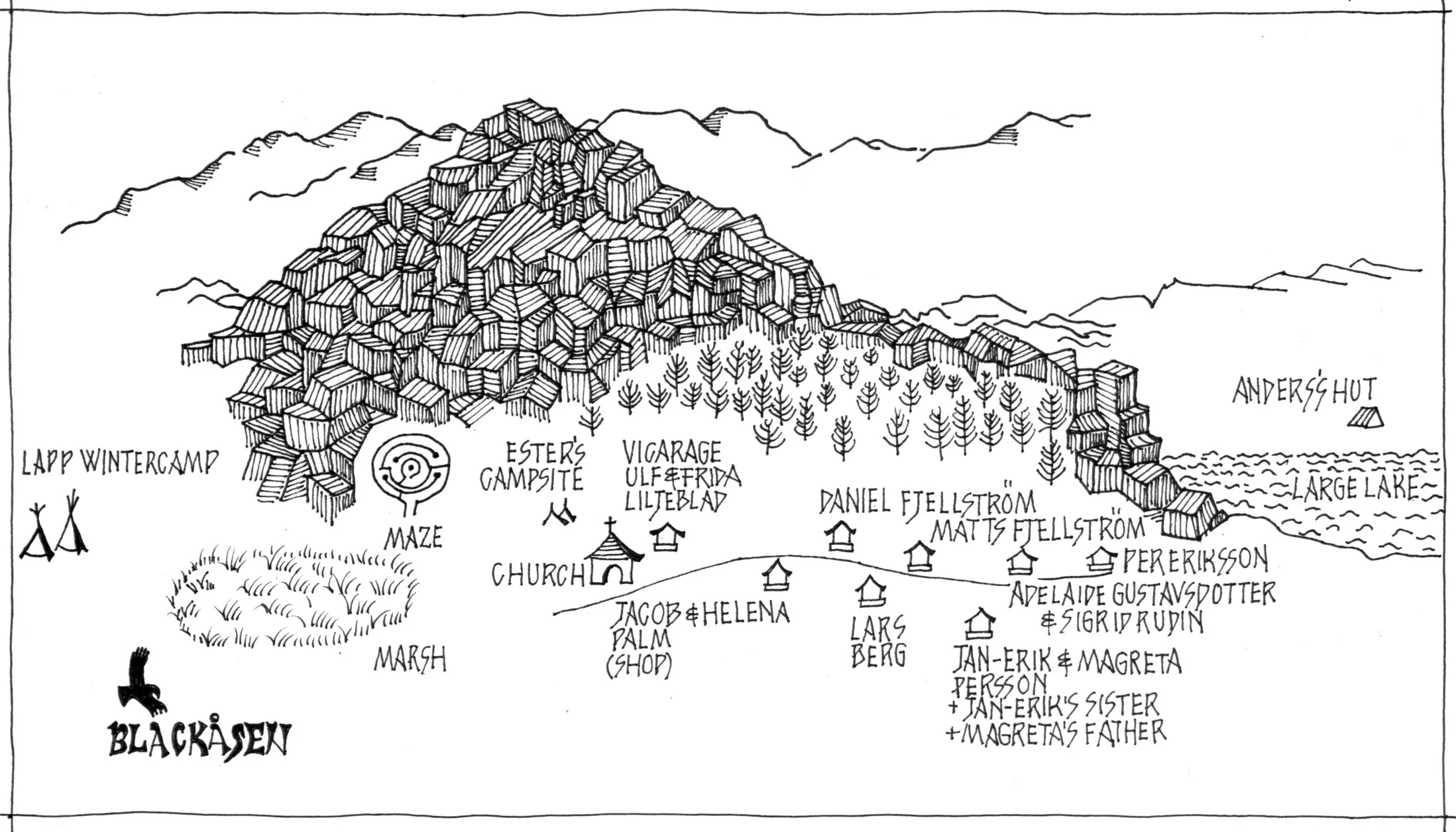

Magnus is a geologist. When the Minister sends him to survey the distant but strategically vital Lapland region around Blackåsen Mountain, it is a perfect cover for another mission: Magnus must investigate why one of the nomadic Sami people, native to the region, has apparently slaughtered in cold blood a priest, a law officer and a settler in their rectory. Is there some bigger threat afoot? But the Minister has more than a professional tie to Magnus, and at the last moment, he adds another responsibility. Disgusted by the wayward behaviour of his daughter Lovisa - Magnus's sister-in-law - the Minister demands that Magnus take her with him on his arduous journey.

Thus the two unlikely companions must venture out of the sophisticated city, up the coast and across country, to the rough-hewn religion and politics of the settler communities, the mystical, pre-Christian ways of the people who have always lived on this land, and the strange compelling light of the midnight sun.

For Lovisa and Mgnus, nothing can ever be the same again.

WRITING IN THE MONTH OF THE MIDNIGHT SUN

I have always been fascinated by journeying and exploring new territory, both in the actual and metaphorical sense. Maps especially intrigue me: how can something ‘factual’ also be subjective so that two people draw two different plans of the same territory? In the Month of the Midnight Sun is a book about maps. How to draw a new map when you find the old one has become obsolete – what to portray, what to leave out? Or, even to some extent, what comes first, the map or the terrain… It is also a story about being lost. Completely, utterly, devastatingly lost. What it feels like when you're not certain you'll find your way back.

After writing Wolf Winter, I kept thinking about Blackåsen Mountain. What would happen to this mountain as time passed? What would be different? What would be the constant thread of what it was like to live near this mystical place? The inspiration for In the Month of the Midnight Sun then came mainly from true story told in passing. At a party at my parents-in-law’s house, a man was telling me how, as a young medical doctor, he had escorted a mass murderer from a distant northern village to the closest town for medical evaluation and sentencing. While he was talking, I was feeding my twins who were then a year and a half old and I didn’t listen. I regretted it. In my mind, I kept coming back to that voyage and what it would have been like for him, the perpetrator and those left behind. I wanted to know.

Having worked Blackåsen as ‘place’ so much in my first book, Wolf Winter, I felt I needed a different way of accessing the mountain and its nature, a deeper level. And so Magnus, one of the main characters, had to become a mineralogist, as we call them today – a geologist – and Blackåsen was given a large deposit of iron. I wanted Magnus to represent what was ‘new’ about society in the 1850s and contrast him with someone who looked upon the world in a very different manner (this later became our Sami character Biijá/Ester). In October 2014, I was having breakfast with my dear friend geologist Mike Daly at Piccadilly in London. The earlier Sami cult was strongly linked to holy places: stones, wood, an unusual stone or rock, or a whole mountain and we were discussing what it might have felt like to a Sami person if a geologist arrived, wanting to dig it up. We also talked about how to draw a geological map from scratch and what someone like Magnus would have known at the time. On an impulse, Mike took me to the Geological Society in Burlington House. It was so early, they had not yet opened and we waited outside on the pavement – me, worried about missing a flight, Mike, who has certainly travelled more than me, unconcerned – and the wait was well worth it. At the Geological Society, The Map that Changed the World (as it is named in Simon Winchester’s book with the same name) is available for viewing. It is the first true geological map of anywhere in the world, depicting England and Wales, engraved and coloured. Quite breath-taking. The map is marked 1815 and it was made by William Smith, a canal digger, who discovered that one could follow layers of rocks, across a nation, then further, making it possible to draw the underside of the earth. To think that this was how our geological understanding began, by the work of one man, is amazing. And there it was, my ‘place’, and how to portray it this second time around.

I now had the setting, the bare bones of a story, and two characters. And then, by chance, I found Lovisa. I had been skiing and at a break I saw this young woman in the canteen. She had the most interesting face; angry, petulant. She was not beautiful in the traditional sense, and yet she was stunning. I felt everyone in that cafeteria was aware of her and, like me, watched her. She’ll be perfect, I thought. She’ll run havoc with poor Magnus.

I began writing In the Month of the Midnight Sun in September 2014 and it was a very strange experience. For the eighteen months I worked on it, it felt like wading through water. I couldn’t seem to map the story out; even three quarters through the book, I had no idea how it would end. I took a break in writing the summer of 2015 and when I returned it felt impossible to pick up the manuscript again. I had to regain access to the story – revitalise it for myself somehow – and thus I changed the tense to present and the writing to first person. I was lucky in that this worked better, and I could see why – the characters are all lost in some way and when you are lost, you are ‘me’, ‘here’, ‘now.’ I still didn’t know how it would end. A very wise friend of mine, the artist Brigitte Mierau, kept saying ‘trust the process.’ And then, as I came to the ending, it was just there for me to write. It was not more complicated than that.

I come away from writing this book having learnt three things. First, the reason for writing has to be simply to write. Nothing more than that. Otherwise you risk losing that ‘first love’ for writing and it becomes a chore and when it is a chore it is very hard to be creative. Second, you can trust the process. There will be ups and downs, leaps and bounds, periods of faith and others of despair. And it is all part of a process you might not understand, but that you can trust to take you where you need to go. And third, I will never again take a substantial break in the midst of a project. To quote Stephen King in his book On Writing: ‘If I don’t write very day, the characters begin to stale off in my mind… Worst of all, the excitement of spinning something new begins to fade…’ There needs to be momentum in your writing. Once, that is lost, it is very hard to regain it.